0

0

In 2010, together with a new generation of activists, he founded the Movement for Democracy Current Forces (MDCF).

The movement works to defend human and workers' rights.

Today, Zarni is the father of a child.

Zarni was a 17-year-old high school student during the 1988 revolution. He quickly became involved in politics against the military junta that replaced the dictatorship of General Ne Win.

He was imprisoned for 9 years from 1989, undergoing torture.

He was a member of the first group that created 88 Generation, former students who decided to resist the junta from within, whereas many others went into exile.

A LIFE AGAINST OPPRESSION

A report in French about the difficulties political prisoners face after their release

A report in French about the difficulties political prisoners face after their release

An interactive map of Burmese prisons

An interactive map of Burmese prisons

A report questions transitional justice in Burma under the National League for Democracy Government

A report questions transitional justice in Burma under the National League for Democracy Government

The website of the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners in Burma

The website of the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners in Burma

A series of articles on the Movement for Democracy Current Forces

A series of articles on the Movement for Democracy Current Forces

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

Mya’s journey

Mya’s journey

Go further

The number of political prisoners who passed through the prisons of the last Burmese military dictatorship, between 1988 and 2011, has been estimated at 10,000.

Some of them had received sentences of more than 100 years. Many died under torture or from lack of care and food during their detention.

In the Burma in transition today, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners of Burma (AAPPB) estimated that in January 2017, 176 political prisoners remained in detention, while 74 people awaiting trial.

At the end of 50 years of dictatorship, in 2011, one of the first measures taken by the Thein Sein Government was to amnesty 1,300 political prisoners. Among them were leaders of the 88 Generation, former students who are widely admired for their involvement in the 1988 summer revolution.

Subsequently, President Thein Sein promised that there would be no more political prisoners by the end of 2013

At the end of the Thein Sein presidency, many activists or political opponents were arrested, essentially for illegal assembly or defamation

Laura Height, a researcher on Burma for Amnesty International, said in the month before the national elections in late 2015:

"Myanmar’s authorities have clearly been playing a long game ahead of the elections, with repression picking up pace at least nine months before the campaigning period started in September. Their goal has been straightforward, take ‘undesirable’ voices off the streets way ahead of the elections and make sure they’re not heard."

Since the elected government of the National League for Democracy in 2016, if activists or farmers are less likely to be imprisoned for the organization of illegal demonstrations, they remain convicted of defamation or insult, by the military, and often on social networks. The state and police administrations are in large part still controlled by former soldiers.

Portrait of Bo Gyi, Chairman of the Association of Burmese Political Prisoners, at the time of a campaign to free the country's many political prisoners in 2010 © James Mackay

Much of this land has either remained fallow since or else has been rented to other farmers.

Zarni, and other activists like Win Cho, encourage and assist these farmers to assert their rights.

North of the city of Rangoon, in Hlaing Thayar district, farmers are fighting to recover land seized during the dictatorship by state authorities.

The land was then resold to private companies.

A BIASED STRUGGLE

An article on impunity related to land grabbing

An article on impunity related to land grabbing

An article on large-scale land grabbing by the army

An article on large-scale land grabbing by the army

An article on the situation today regarding the numerous historical cases of land grabbing perpetrated by the Burmese military

An article on the situation today regarding the numerous historical cases of land grabbing perpetrated by the Burmese military

Land at the heart

of national reconciliation

Land at the heart

of national reconciliation

A perspective on the problem of land with the film

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

Mya’s journey

Mya’s journey

Go

further

After the Thein Sein government took office in 2011 and the relative "democratization" of the country, the impunity of land "thieves" was challenged.

Yet the policies put in place by the government seem contradictory. On the one hand, the Government established a parliamentary Land Investigation Commission and a conflict resolution council. On the other, Parliament adopted a series of laws favorable to agribusiness.

Therefore, opening up the country and the increased local and foreign investment it promised increased speculation on land. It was accompanied by a new wave of land grabbing, in a context where the rule of law is still absent.

At the same time, seeking to recover their land, farmers were in conflict with various ministries, the army and cronies at a time of relative freedom of speech.

Examples of land grabbing range from occupation without compensation by army battalions in the central plains 20 years ago to international biofuel companies that are offered immense fertile areas in ethnic regions.

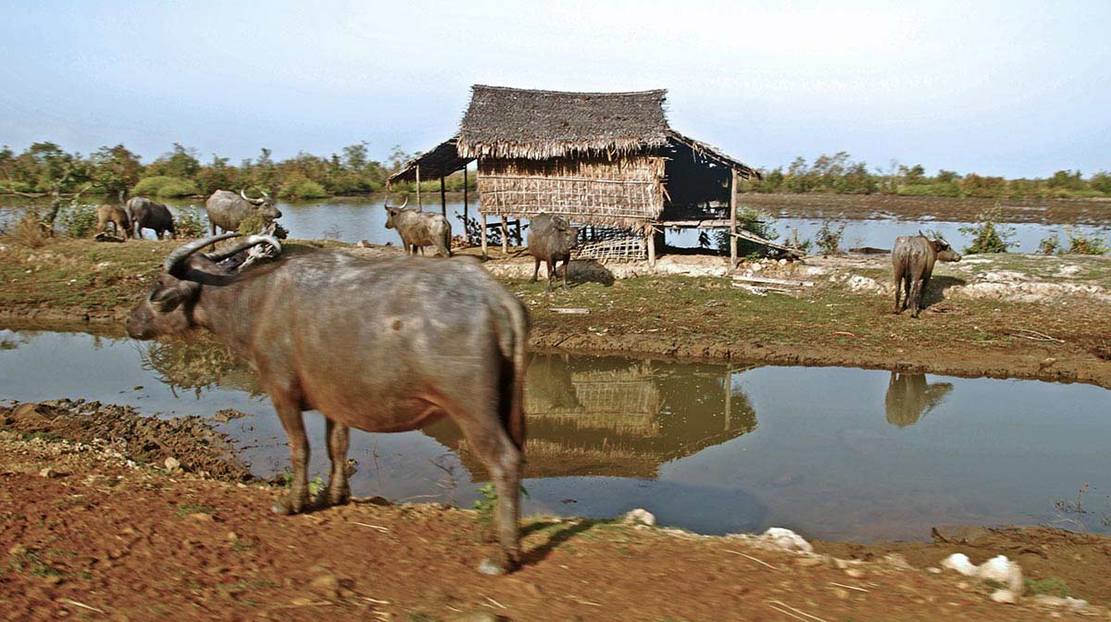

Farmhouse in the center of Arakan

Legislation stipulates that

all that is under and on earth belongs to the state.

It dates back to the English colonial era and has never been canceled. New texts have simply been added since. At the same time, by tradition among the farmers, land ownership was governed by a "first to use it is the beneficiary" principle.

After independence, during the 10 years of democratically elected government of U Nu, then during the fifty years of military dictatorship that followed, the complexity of land ownership laws and the impunity of the rulers means that, practically, the rule of law had was replaced by a situation in which all rights passed to the military.

In Burma, 70% of the population is linked to the agricultural sector. Half of this agricultural population are small farmers who typically work less than 2 ha and who have never enjoyed any protection.

The army, its entrepreneurial friends (cronies) and all levels of the state (national, regional and local) have continued to appropriate land worked by farmers, generally offering no compensation.

In 2013, after the Government announced an increase in the price of electricity, they initiated a rally against this increase. Consequently, several members of MDCF are on trial for violation of “Article 18”.

As soon as relative freedom of expression was in place, Zarni and the Movement for Democracy Current Forces (MDCF) organized, often in conditions of emergency, demonstrations with farmers and workers, in pursuit of the fair application of their rights.

ILLEGALLY DEMONSTRATING FOR THE RIGHT TO PROTEST

A video report on the new tools for criminalizing peaceful protest and infringing on freedom of speech

A video report on the new tools for criminalizing peaceful protest and infringing on freedom of speech

“They can arrest you at any time” - a report on the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Burma

“They can arrest you at any time” - a report on the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Burma

Amnesty International report on inadequate changes to the law on peaceful assembly in 2014

Amnesty International report on inadequate changes to the law on peaceful assembly in 2014

A 2012 report on the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act

A 2012 report on the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

Mya’s journey

Mya’s journey

Go further

The international community applauded the first steps taken by the Thein Sein Government: the release of more than 1,300 political prisoners, the liberalization of the economy, greater freedom of expression for the media and the public.

Under the dictatorships, all public gatherings of more than five people were prohibited. As early as 2012, the Government passed a law on demonstrations: it is found in section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law, and is commonly referred to as “Article 18”.

It states that in order to organize a demonstration, the permission of the local authorities must be requested five days in advance, the names of the leaders and of any prominent figures who will be participating must be given and all leaflets and slogans that will be used must be submitted. Permission to organize the demonstration depends entirely on the local authority. The text of the law is not very different from those of some Western democracies.

What differs is the way the law is applied. In the first year after the passage of the law, local authorities granted permission to stage demonstrations in a totally biased manner. By 2015, with further elections approaching, the law was being used to arrest activists.

For human rights activists in Burma, in terms of freedom of expression, a shift there has been a shift from control and prohibition through censorship to less direct constraint through the criminalization of actions. The new law promoting freedom of expression has turned into a "new generation" instrument of repression instrument, whereby, through the use of legislation, repression by the authorities is "acceptable" in the eyes of Western democracies.

Immediately after it was enacted, in 2012, civil society came together to signal its opposition to “Article 18” of this law. Most of the law’s opponents remained unsatisfied with a modification made to the text in 2015. Since the NLD government took office, parliament has debated further changes to the law.

Demonstration in the center of Yangon in 2012 against the law known as Article 18, used by the authorities to prevent demonstrations being held

Meanwhile, Zarni’s understanding of human rights is based on those set forth in the Universal Declaration. These rights apply to all, regardless of gender, religion, social origin... He is especially concerned with the most oppressed, farmers, workers, but also people of Muslim faiths suffering from the increase in discrimination in recent years.

In his educational work, Zarni draws on the positive aspects of diversity in a context of globalization that is often misunderstood.

Since 2011 and the opening of the country to parliamentary institutions, many former political prisoners have resumed their activities as human rights defenders.

One subject continues to divide them, however: the place of Muslims in the country, in particular that of the Rohingyas. People emblematic of the 88’s revolution movement do not shy away from using anti-Muslim rhetoric, even though they remain a symbol of the struggle for human rights. This apparent contradiction reflects the complexity of the position of this Muslim minority in Arakan and of interreligious relations in contemporary Burmese society.

APPLYING THE BUDDHIST PRACTICE OF "METTA" FAIRLY

Blog of a former member of the Burmese military, spreading anti-Muslim propaganda

Blog of a former member of the Burmese military, spreading anti-Muslim propaganda

An initiative for peace between religious groups

An initiative for peace between religious groups

A 2000 report analyzing the extent of discrimination by the Burmese state against the Rohingya minority

A 2000 report analyzing the extent of discrimination by the Burmese state against the Rohingya minority

A 2003 article on nationalist monk Ashin Wirathu

A 2003 article on nationalist monk Ashin Wirathu

Those buddhists that exclude

Those buddhists that exclude

A perspective on religious tensions with the film

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

Mya’s journey

Mya’s journey

Go further

Their places of worship have been destroyed. Also, as in other regions occupied by ethnic minorities, they have been the victims of forced labor, theft, arbitrary arrest and torture.

More precisely, in 1982, a law deprived the Rohingyas of citizenship by refusing to recognize them as one of the country’s 135 ethnic groups. They had to return their identity papers in exchange for temporary "white cards". Whole villages were displaced to make way for Buddhist inhabitants. Properties and land were requisitioned. Access to public services in education and health was prohibited.

In 2012, a wave of violence in Arakan state caused the death of more than 250 people, mostly Rohingyas. A further consequence was the displacement of 150,000 Rohingyas to refugee camps, with very limited access to food and health-care.

Finally, in 2015, all holders of "white cards" (including Chinese and Indians) were obliged to surrender their temporary identity cards to the authorities, receiving nothing in exchange and thereby becoming illegal foreigners. A few weeks later, Parliament passed a law prohibiting them from voting in and contesting the forthcoming election in November, rights they had enjoyed since independence.

A further outbreak of violence occurred in this state, in October 2016. An attack on police border posts by Rohingyas potentially linked to an international Muslim terrorist movement resulted in a complete shutdown of part of the State. The army and the Burmese police prevented all media and NGOs from entering the territory. For several weeks, the Rohingya population was allegedly subjected to destruction of property, rape and murder. Several international experts spoke of a genocidal intent on the part of the country’s authorities.

Throughout Burmese history, state-organized discrimination has been supported by an extreme nationalist fringe, whose leaders are members of the monastic community. They claim they are militating for the defense of race and religion. Their abiding obsession, which predates the contemporary radicalization of a minority of Muslims, is the invasion of their country.

As a result of the 2014 census, it is now known that all Muslims in Burma represent 5% of the population.

The first Muslims to settle in Burma were Arab and Persian merchants, in the ninth century, before the establishment of the first Burmese Empire of Bagan (Around the year 1000). Established mainly in port cities, they have mixed naturally with local populations.

Others arrived from neighboring countries by land, from what today is India and Bangladesh. They first settled in the north west of the country, the location of today’s Arakan state. Others came from the present-day Yunnan province of China. These are the Pathay, today still established mainly in the Mandalay region in the centre of the country, and Pathein, in the Irrawaddy delta. Then, during the British colonial era, Hindus and Muslims were moved from India to meet the need for labor in agriculture or in the country’s administration.

Throughout the history of Burma, Muslims, who still represent a very small minority (less than 5% of the population at the last census, in 2014), have suffered several waves of discrimination, sometimes at the hands of the population, sometimes directly orchestrated by the State and the army.

From the 15th to the 18th century, the population was Buddhist and Muslim. The Muslim culture of the surrounding sultanates influenced the court of the Arakan Kingdom. When the Burmese empire occupied Arakan in the 18th century, the army eliminated part of the Muslim community and enslaved another part, transporting them to the center of the country.

In the same region, during the Second World War, both the Japanese and the Burmese (at that time allied) committed atrocities against the Muslim population.

Ne Win, the notoriously xenophobic Burmese dictator from 1962 to 1988, launched a major military campaign, "Operation Dragon", to verify the origin of the inhabitants of Arakan. This campaign turned into a witch-hunt against Muslims, who were prompted to flee to neighboring countries.

Among the Muslim population of Burma, the Rohingyas are the most numerous. Since that time up until the present, their rights have gradually been restricted. Treated as second-class citizens, they are denied freedom of movement. A request to the authorities is necessary to leave their places of residence or for example to get married. Since the 1970s, they have not been allowed to work for the State, the police, in administration or education.

Since 2012, enjoying greater freedom of expression, residents around the mine, together with activists and monks who support them, have denounced the methods used by companies, which compound human rights violations: land confiscation, environmental damage, verbal and physical violence, including the death of a woman farmer, killed by a police bullet.

A few months previously, in early 2014, Zarni came to Letpadaung to gather testimonies from villagers following another confrontation with local police and the mining company’s security force.

The copper mine project in Letpadaung, in the center of the country, was initiated during the Burmese dictatorship. One of the biggest conglomerates in the country owned by the army, the Union of Myanmar Economic Holding Ltd (UMEHL), took possession of the land in order to allow ore to be extracted.

After a trial with a Canadian company, UMEHL offered operating rights to a state-owned Chinese enterprise, Wan Bao, for 60 years.

No study of the social and environmental impacts on the local population of the 26 surrounding villages was conducted before work began.

LETPADAUNG, "IRRESPONSIBLE" INVESTMENT EXEMPLIFIED

The example of Chinese investment in the territory of the Ta'ang ethnic group in the Shan region

The example of Chinese investment in the territory of the Ta'ang ethnic group in the Shan region

An overview on foreign investment in Burma

An overview on foreign investment in Burma

A 2017 report by Amnesty International on problems related to the operation of the Letpadaung mine

A 2017 report by Amnesty International on problems related to the operation of the Letpadaung mine

In the shadow of the mountain that no longer exists!

In the shadow of the mountain that no longer exists!

A report on the situation in Letpadaung at the end of 2014

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

Mya’s journey

Mya’s journey

Go further

Having hitherto controlled all sectors of the economy, the army now relinquished parts of the profitable sectors (oil, mining, the food industry) to loyal oligarchs.

For two decades, only a few neighboring countries ignored the opaque and repressive policy of the junta, investing mainly in large infrastructural and industrial projects. The direct consequences for local populations are often more human rights violations.

In 2011, the process of opening and democratizing the country initiated by President Thein Sein led to the phasing-out of Japanese and Western economic sanctions (except those applied to arms). The Government is seeking to attract foreign capital by granting tax concessions to foreign investors and liberalizing its investment rules.

As the country has abundant and diversified natural resources, very cheap labor and an exceptional geographical position between the world’s two biggest markets, China and India, it is certain that many international companies will invest over the coming years. Military companies and their cronies control key sectors of the economy, effectively forcing foreign investosr to cooperate with them.

In 2012, Aung San Suu Kyi explained that:

Foreign investors should wait a little, for their own good and for that of the country. (... / ...) There is no point in having investment laws until there is a strong judicial system that ensures that laws are enforced.

Yet, once the NLD took office in 2016, the latest US sanctions (with the exception of arms sales, to which the European Union also applies sanctions) were lifted.

During the English colonial period, Burma became the most developed country in South-East Asia.

It was the world's largest rice exporter.

After independence, Burma became one of the few countries to leave the British Empire without joining the Commonwealth. Caught between multiple guerrilla conflicts, over a decade the country’s economy declined. In 1962, the choice of the first Burmese dictator, General Ne Win, was to isolate the country from the international scene by pursuing the "Burmese way to socialism".

The country's economic decline occurred in parallel with the loss of the population’s most basic rights. The army controlled the whole of society and the economy. The country became and has remained one of the poorest in the world.

From 1988, the second military dictatorship sought to end the country’s isolation by seeking to attract foreign investment, but Western countries responded with sanctions following the bloody repression by the military of a widespread popular uprising.

In a context of widespread corruption, the Burmese economy is characterized by government monopolies, conglomerates owned by the military, the absence of a legal framework and an independent judiciary, the massive laundering of money generated by trafficking (in drugs, precious stones and wood) and a total lack of transparency and responsibility on the part of the authorities.

Zarni, who comes from Rangoon, and Myint Aung Thein, who comes from Mandalay, conduct this one-day meeting. This is a rare opportunity for the local population to listen to agricultural experts, FNI officials and political figures.

Together, they provide an overview of the Burmese peasantry which is now opening up to foreign markets.

The Farmer Network with the International Labor Organization (FNI) has issued an invitation to several members of the Movement for Democracy Current Forces (MDCF). This organization is one of the strongest in the north of the country, comprising farmers and workers.

It focuses on labor rights, especially those of farmers, but also on human trafficking, child soldiers and support for former political prisoners.

SHARING EXPERIENCE AND KNOWLEDGE

A study on the work of Burmese activists against dam projects in ethnic areas

A study on the work of Burmese activists against dam projects in ethnic areas

The view of a Western economist on the needs of the rural Burmese population

The view of a Western economist on the needs of the rural Burmese population

An interview with Dr Thaung Htun about the work done with his association, the Institute for Peace and Social Justice

An interview with Dr Thaung Htun about the work done with his association, the Institute for Peace and Social Justice

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

Mya’s journey

Mya’s journey

Go further

However, groups of young people, such as "Generation Wave" and musicians opposed to the regime, became a new political force at the end of the military junta, particularly during the "saffron" revolution in 2007. While the majority of the youth are seeking access to a consumer society, in recent years, in the cities, rural areas and remote ethnic regions, a new generation has begun to understand that it is their responsibility to design the future of their country.

Today, however, those who are pushing for "freedom from fear" and calling for the rule of law, are still first and foremost the old generation of students of the 88 revolution, known as "88 Generation and open society". Living mainly in urban centers, they are mostly former political prisoners with nothing to lose. They are pushing the authorities to speed up the democratization process, as is the historical opposition party, the National League for Democracy, the party of Aung San Suu Kyi, which was reauthorized in 2010.

In 2015, a new generation of students, active in politics, emerged. During the passage of a law on education, which they were challenging, several hundred of them converged from all over the country on Rangoon, holding peaceful marches. Blocked about 100 kilometers from the city, their movement was stopped by a violent police charge. Seventy of them spent a year in prison before being amnestied when the new Government of the National League for Democracy took office, in April 2016.

Activists, former political prisoners, students and members of democratic political parties are all well aware of the pressing need for the widest possible involvement of the population, not least the 70% of the population in rural areas. Since the opening of the country, many have endeavored to meet with the rural population and defend them. Without their support, rural people would not be aware of changes to government policy. Exchanges with activists and members of democratic political parties are an essential first step in building the collective awareness essential for advancing the rights of all.

Fifty years of dictatorship,

one of the most repressive

in contemporary history, condemned generations

of Burmese to live in fear,

in conditions where

"fear is a habit",

as Aung San Suu Kyi has said.

Surviving in miserable conditions, most Burmese forgot about the responsibilities normally entrusted to the State and their own rights as human beings.

Consequently, when the Thein Sein Government, comprising mainly former military officers, was formed in 2011, hope among the population of any improvement in quality of life was low. The first year of Government reforms surprised both Burmese educated circles and the international scene.

The release of political prisoners, macroeconomic-oriented economic reforms and progress in freedom of opinion had little impact in rural areas, where corrupt practices and rights violations by the local authorities are entrenched. Here, life is above all focused on meeting basic needs and the population has despaired of political practice for generations.

Historically in Burma, students have always been at the forefront of political and social demands. This was the case throughout the 20th century, in the struggle against colonization and dictatorship, but the closure of universities during the 1990s has made a broad renewal of the student population difficult.