0

0

Together with her companion, she established the New Myanmar Foundation (New Myanmar Foundation, NMF).

With an initial focus on environmental issues, from 2008, her organization turned to monitoring the elections held in 2010.

The group also provides education on human and social rights and participates in the country’s peace movements.

Mya Nandar is a Buddhist. Her family is of mixed Burmese and Pao origins, the Pao being an ethnic minority from Shan State.

Her parents were civil servants stationed in different parts of the country before settling in Yangon.

After studying business, she was involved in helping victims of Cyclone Nargis in 2008.

GRASPING THE MEANING OF DEMOCRACY THROUGH ELECTIONS

'The story behind Burma's Election 2010' is a documentary produced by the Democratic Voice of Burma

'The story behind Burma's Election 2010' is a documentary produced by the Democratic Voice of Burma

An overview on the 2010’s elections

An overview on the 2010’s elections

Zarni's journey

Zarni's journey

Nini's journey

Nini's journey

The Army refused to recognize the result, annulled the elections and remained in power until 2010.

The writing of a new constitution took 15 years and was approved by 93% of the population in a referendum in 2008. This was the third step of the road map toward democracy initiated by the military junta. The fourth was the 2010 elections, boycotted by the Burmese opposition and ethnic parties. The junta party gained 57% of the vote, and, in accordance with the constitution military officers also occupied 25% of the seats.

In 2012, by-elections were held, in which the NLD participated, winning 43 of the 44 contested seats. This was the first election with a minimum of legitimacy and marked the beginning of the current period of transition to "disciplined democracy", as desired by the military.

National elections were held at the end of 2015, with a participation rate of 80%. The NLD won over 60% of the vote, despite irregularities in respect of voting by expatriates and in the offices of the army (500,000 men). These elections were nonetheless considered to have been free and fair. Alongside the NLD, the military party (USDP) received only 5% of the vote, barely more than the strongest ethnic party, the Arakan National Party. The latter and the Shan , Nationalities League for Democracy are the only two ethnic parties to have received a minimum of popular support. Surprisingly, the NLD won the ethnic vote.

Although the constitution reserves 25% of the seats (a total of 166) for the army, the NLD party secured 390 of the 498 elective seats in the two national assemblies of the country. It was able to appoint its president (Aung San Suu Kyi was excluded by the constitution), U Htin Kyaw, an intimate of Aung San Suu Kyi and one of the vice-presidents. The second is chosen by the army.

Voting day in Yangon in 1960

The first election dates back to 1922, when Burma was still a province of the British Indian Empire. 6% of those eligible to vote elected 80 members of the Legislative Council, whose 50 other members were appointed by the British colonial authorities.

Elections were subsequently held in 1925, 1928, 1932, 1936 and then in 1947, a few months before independence. The central theme was always separation from the British Indian Empire. In 1947, turnout reached 50% despite a boycott by several parties.

The first general elections in independent Burma took place in 1951 and 1952, because voting was delayed in some areas where a civil war was being waged. Turnout was 20%.

Elections took place in 1956 and 1960, with turnout in 1960 reaching 66%, the highest so far. Yet, by 1958, the army had formed an interim administration to run the country. And in 1962, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, General Ne Win took power, retaining it thereafter until 1988.

During his dictatorship, three one-party elections were held (1978, 1981, 1985), with turnout close to 95% on each occasion.

After several months of protests in 1988, the '88 Revolution' broke out in the country, with students, monks and the people calling for democracy. The army overthrew the previous dictator and suppressed the uprising, killing between 3,000 and 10,000 people. It formed the State Law and Order Restoration Council, which promised elections for 1990.

The party of Aung San Suu Kyi, the National League for Democracy (NLD), and ethnic allies won almost 80% of the seats on a turnout of 50%.

The New Myanmar Foundation (NMF) participated in the creation of the Bayda Institute in 2011. The institute is one of the leading think tanks linked to the NLD today.

The NMF and the Bayda Institute were among the first civil society groups to organize themselves in preparation for the 2015 elections.

Mya, as an expert on the electoral process, met members of the Bayda Institut. Together they will find and train observers for the national elections in late 2015.

CREATING A BASE FOR OBSERVING THE ELECTIONS

The website of Election Education and Observation Partners

The website of Election Education and Observation Partners

The mission of Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL) for the observation of elections in Burma

The mission of Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL) for the observation of elections in Burma

An article describes the excitement in civil society at the beginning of the democratic transition, at the Bayda Institute and elsewhere

An article describes the excitement in civil society at the beginning of the democratic transition, at the Bayda Institute and elsewhere

The Info-Birmanie film about the elections of November 2015

“Towards a burmese transition?”

“Towards a burmese transition?”

Zarni’s journey

Zarni’s journey

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

-The Electoral Commission of the Union of Burma (UEC) was created in 2010. It is the body responsible for organizing and overseeing elections. It is the final arbiter in the event of disputes. The opposition has criticized the partiality of the UEC because the president appointed its members, and most of them are ex-military. Its president, U Tin Aye, was elected as an USDP MPin 2010, just before being appointed. Since taking office, President Htin Kyaw has appointed the five new members, as it is written in the constitution.

The last partly free elections to be held throughout Burma were those organized in 1990 (with the exception of a few constituencies where there was civil war). But in view of the disastrous result it achieved, the party of the military annulled the elections and retained power for another 20 years.

Previously, no free elections had been held throughout the entire territory, even during the decade of the Republic of Burma following independence. Civil wars had already begun and whole swathes of territory were no longer under the control of the central government.

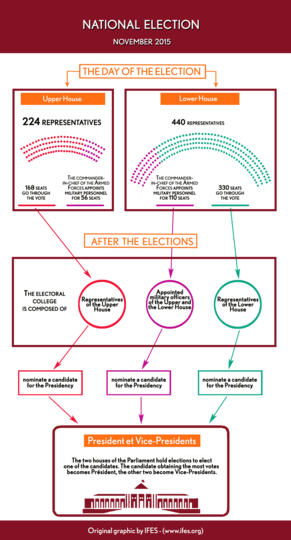

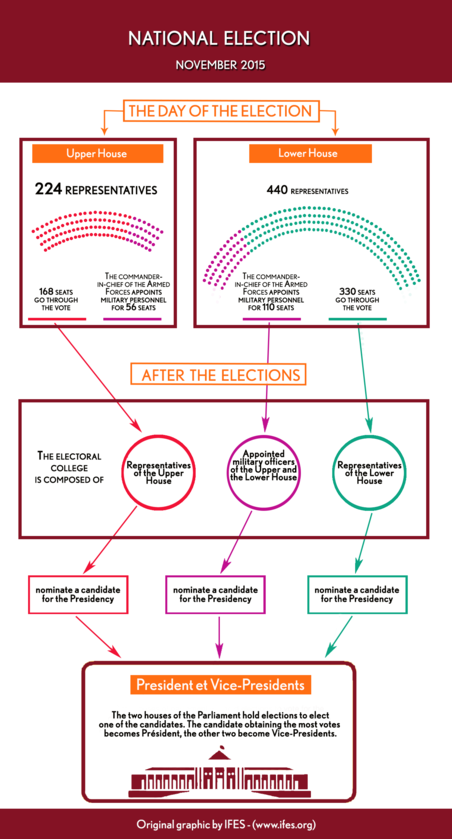

The 2015 elections in figures:

-The electorate numbered almost 32 million.

-46,000 polling stations.

-93 political parties participated.

-1,171 seats were contested by 6,189 candidates: 224 for the Upper House (the equivalent of the Senate), 440 for the Lower House (the Parliament), with the 507 remaining seats distributed among the assemblies of the 7 Burmese regions and the 7 ethnic States.

-Women represented less than 10% of candidates in all parties, apart from the NLD(15%) and the National Democratic Forces (NDF, 20%). There was also a party called the Women's Party in Mon State, whose women candidates contested only a few constituencies. In the new assemblies, women represent less than 10% of elected officials, but twice more than the previous legislature.

-Constitutionally, 25% of seats in all the assemblies are reserved for the military. But many former rank officers are also on the lists of most of the parties. For example, they represent 79% of the members of the executive central committee of former President Thein Sein’s party, the Union, Solidarity and Development Party (USDP).

-The elected representatives of the Upper and Lower House will elect the next president from three candidates: one for each House and one for the military (see graphics). President Htin Kyaw was elected because constitutionally Aung San Suu Kyi could not apply for the post. But as soon as the government took office in April 2016, parliament voted for the creation of a special adviser to the president (the equivalent of a prime minister).

A report on the situation in Kachin state before the arrival of the peace march

A report on the situation in Kachin state before the arrival of the peace march

An article about the arrival of walkers in Laiza

An article about the arrival of walkers in Laiza

A perspective on the peace march in the peace process

A perspective on the peace march in the peace process

A perspective on the peace process of the longest ethnic civil war in the world with the film

A powder keg of ethnic diversity

A powder keg of ethnic diversity

Zarni’s journey

Zarni’s journey

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

Then, two months later, civilians living in Kachin refugee camps travelled to Yangon in order to publicize the difficulties they faced. Some young people were moved by their testimonies to organize another peace march, from South to North, to the places of armed conflict, in the state Kachin. Local people discreetly offered them food and shelter and monks also provided assistance.

The group, initially numbering a few dozen people, wanted to persuade both the urban and the rural population to challenge the need for the central army to wage war.

Three weeks after the start of the march, peace activists Mya and Win Cho (who is renowned for his determination) were called in support by the leaders of the march.

With the arrival of the Thein Sein Government, some real reforms brought about change, mainly in urban centres. A new, relatively greater freedom of expression led the population gradually to claim its rights, among other means by demonstrating. Even if the subject was still sensitive, the media had a narrow opening to discuss the fighting in the country between the army and ethnic groups, whereas hitherto they had either been censored or served to broadcast the military junta’s propaganda.

Some sections of the Burmese people had strong feelings about the fighting taking place on their doorstep. In September 2013, in Yangon, a peaceful march was organized, calling for the end of hostilities.

GAINING THE SUPPORT OF THE RURAL POPULATION FOR THE DEMAND TO CEASE HOSTILITIES

The army refused to accept any dissenting voices, either among the minorities or the Burmese opposition. Its only concession was to allow some to manage parts of their mountainous and underdeveloped territory.

When the military junta drew up a constitution that defended its interests in 2008, it asked all ethnic armed groups that had signed bilateral ceasefires to become Border Guards Forces (BGF) under its wing. All major ethnic groups rejected this proposal and after 2009 armed conflict resumed on several fronts. These were focused in particular on the busy road to trade with China, places where major industrial projects were under development in Shan and Kachin States.

In 2010, the army had one of its own high-ranking officers elected as the head of the country, former general Thein Sein. He announced that interethnic peace was one of his priorities in 2011. He committed his Government to a national ceasefire process, but, at the same time, the army continued to wage war against several ethnic armed groups of the North East region, seeking to expand as much as possible its control over these territories. The civilian population fled the fighting and the bombing, abandoning their villages. Many have been living in refugee camps for several years.

In the colonial era, the British pursued a policy of "divide and rule" throughout Burmese territory. On the one hand they played the Burmese majority against ethnic minorities, leaving them a degree of autonomy in their mountainous territories, and on the other they concentrate their efforts on exploiting the wealth of the central plain.

After 150 years of colonization, at the end of the WWII, minorities believed that their special status would continue after independence. A historic meeting called the Panglong Conference was moving in this direction, with the gathering of ethnic leaders and General Aung San (father of Aung San Suu Kyi), national hero and leader of the country. After he was assassinated a few months later, autonomy was no longer on the agenda.

Ethnic guerrillas then began destabilizing nascent Burmese democracy. A decade later, in 1962, the Burmese army, headed by General Ne Win, staged a coup. This signalled the beginning of 26 years of brutal military dictatorship, especially for ethnic minorities, marked by the confiscation of land, arbitrary arrests, imprisonment, torture, rape and murder.

After the fall of Ne Win at the end of the 1980s, while some ethnic groups obtained an armed peace in bilateral agreements with the second Burmese military dictatorship, they were never granted the rights they expected to receive.

Mya and Win Cho joined the group so it could benefit from their own experience in its daily trials with the authorities.

Since the beginning of the peace march joining Yangon with the front zone in Kachin State, every step has been a trial for the group of young people taking part.

THE SAME TRIAL REPEATED AT EVERY STEP

An article on the border police, one of the Burmese services that has committed many human rights abuses against civilians

An article on the border police, one of the Burmese services that has committed many human rights abuses against civilians

Investigation paper on Swan Arr Shin, a group of civilian thugs used by the police

Investigation paper on Swan Arr Shin, a group of civilian thugs used by the police

An overview of the peace process by International Crisis Group

An overview of the peace process by International Crisis Group

An article on the problem encountered just before the end of the march

An article on the problem encountered just before the end of the march

Zarni’s journey

Zarni’s journey

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

Dating back to the colonial era, the “communes and villages administration law” allows the police to come and check the list of residents in any dwelling at any time of the day or night. This law was used to oppress dissidents and their families during the dictatorship. It was also used as recently as March 2015 for the nighttime arrest of students taking part in peaceful demonstrations.

During one of these student demonstrations in the centre of Rangoon, a group of civilians was recruited by the local administration to violently repress the peaceful protest. These recruits are called "masters of force”. Ex-convicts are often prevailed upon to participate, with a refusal bringing reprimands. Here again, this law dates from the colonial era.

In 2003, these "masters of the force", armed with knives, attacked an NLD convoy in a remote location in the north of the country. Four members of the NLD were killed and dozens were injured, while Aung San Suu Kyi, the target of the attack, narrowly escaped.

For a long while, these laws from another time were used by the dictatorships to repress political opponents, a legislative arsenal that allowed them to hold their heads up before the international community and to claim to uphold the rule of law.

The Government that came to power in 2016, the first elected Government for decades, does not have control of the police. Constitutionally, the minister in charge of them, the Minister of Home Affairs, is appointed by the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

However, Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, which has an absolute majority in the country’s two assemblies, has been able to modify the “communes and villages administration law".

For several years now, Burma's new Western partners, such as the European Union, have been working with the Burmese police, providing training, for example, on how to act with respect for human rights during violent demonstrations.

Police officer stops a young man on a moped in the Dala district of Yangon

The current Burmese police is a continuation of the force established by the English in the early nineteenth century. Some of the laws they apply also date from more than a century ago.

During the dictatorship of General Ne Win, the Burmese army became a state structure above the administration, gradually taking responsibility for virtually all government functions at all levels of the state. The army assumed the role of the police in maintaining order.

In 1974, the only mission of seven police battalions based in Yangon, Mandalay and different ethnic States was the suppression of protests and popular uprisings. The police had become an auxiliary of the army, a component of the extensive Burmese services for defense against both external and internal enemies.

For this reason, the police never enjoyed a positive image among the population, especially after the 88 Revolution, which was suppressed by both the police and the army at the cost of thousands of lives. Corruption at all levels of the police further tarnishes their reputation. One example of this is the protection by the police, visible to all, of lucrative and illegal business activities.

In 1995, the police changed their name to the Myanmar Police Force. Their mission is twofold and contradictory. On the one hand, they serve to protect the population against crimes and other threats, requiring mutual trust. On the other, they must guarantee public order, which means, under a dictatorship, the pursuit of political dissidents and the obstruction of all those somehow seeking to combat the established political order.

For this second mission, during the colonial period, the police intelligence services were established. Under the dictatorships, the "Special Branch", the plainclothes political police, had informants in every neighborhood, on every street. Keeping the whole population under surveillance for decades meant that "fear became a habit", as Aung San Suu Kyi has written.

The population must declare all the people who reside in a given dwelling. A mandatory list is regularly updated by district administrations. Even having a guest stay for a single night requires the declaration of that person.

The weekend of the BarCamp was given over to workshops, brainstorming sessions and conferences such as that organized by members of Generation 88. The coming year’s elections were one of topics aired among attendees.

In January 2014, Mya found time to spend a day at the BarCamp in Yangon, in the company of other people interested in information and communication technologies.

URBAN, BUSY AND CONNECTED

Analysis of the use of social networks for hate campaigns against the Muslim minority, the Rohingyas

Analysis of the use of social networks for hate campaigns against the Muslim minority, the Rohingyas

An 2014 article assessing the digital revolution in Burma

An 2014 article assessing the digital revolution in Burma

An example of social media use for social purposes

An example of social media use for social purposes

An article on using social media for the election campaign

An article on using social media for the election campaign

An article on the 1st BarCamp of Yangon

An article on the 1st BarCamp of Yangon

Zarni’s journey

Zarni’s journey

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

This is in stark contrast with the years that followed the Saffron revolution (2007), when 15 fifteen journalists, bloggers and activists received prison sentences ranging from three to dozens of years for having criticized the authorities, circumvented censorship or had contact with foreign media via the Internet.

This is the backdrop to the first Bar camp in Burma, held in 2010: a meeting for those wishing to find out more about new technologies, with all those wishing to talk about a topic before an audience able to do so. Bar camps and tech camps are an opportunity for many Burmese and civil society groups to meet and learn from local and international experts in the field of information technology.

Between conferences and workshops, the emphasis is on collective initiative to find technical solutions to the problems encountered by civil society. Anyone is free to present a subject before an audience. 2,700 participants attended the first Bar camp in Yangon, more than for any other Bar camp in the world.

Supported subsequently by various American institutions, Myanmar ICT for Development Organization (MIDO) organizes bar camps and also tech camps. Its chairman is one of the bloggers imprisoned in 2008: Nay Phone Latt. He was released in a presidential amnesty in 2012.

The country has gone from the total censorship of information under the dictatorships to the relative freedom of media that also use social media. This sudden freedom of expression, whereby a message can spread rapidly on social media, brings with it rumors, disinformation and insults. And without an adequate legal framework, expressing opinions in public has again become a sensitive issue in the country. Since the elected Government of the National League for Democracy took office, nearly a dozen people have been pursued for defamation after publishing on Facebook, both ordinary citizens and journalists.

Jour de vote à Yangon en 1960

Young man in central Yangon in 2012, soon after the cost of a mobile phone became generally affordable

In 2006, anyone from Burma wanting to purchase a SIM card had to pay 2,600€. Today, the cost is 1.3€.

Between 2010 and 2015, the rate of mobile penetration among the Burmese population increased from 2.7% to 32%.

Mobile network coverage in the country was 10% at the end of 2013. The goal is to reach 75% in 2018.

The arrival of two foreign companies on the Burmese market in 2014 has completely changed the telecommunications landscape. Burma has the third highest rate of mobile phone sales growth, just after its two big neighbors, China and India. In mid-2012, 1% of the population used the Internet. It has been estimated that this will rise to 80% in 2017, thanks to drastic reduction of prices for mobile phones and telecommunications.

The country is the first in the world where Internet users overwhelmingly connect via a mobile phone. Unlike all the countries that have developed the market for new technologies with computer support, in Burma the phone has immediately become the standard support.

In 2011, Facebook was inaccessible in the country. Today, more than 60% of Internet users have a Facebook account, a large open window on the world compared to a few years ago when only the urban and privileged few could escape the country via the web.

So for many today, the internet is Facebook!

The Government and ministries make also their official statements via this social network...

At a crossroads, a policeman receives a sum of cash from a bus driver. This situation of corruption was filmed on a mobile phone. The scene circulated on social media and scandalized the population. As the freedom of speech increases, so too does citizens’ awareness. The mobile phone is no longer just for making phone calls.

Samantha Barry has worked for the BBC.

She travels the world to train citizens in using smartphone in place of cameras. The challenge is both to facilitate associations’ communication on social networks and to foster committed citizenship by this means.

Thanks to their local partners (Rhododendron Indigenous Development Association and the Tedim Youth Fellowship), about 30 people gathered for training each day.

The objective was that these people should, in turn, educate the population in the areas where they live.

The New Myanmar Foundation organized training, talking about the bases of parliamentary democracy. Mya and her colleague leave Yangon for a week to travel in remote north ethnic areas.

The group has established partnerships with associations around the country.

THE NEED TO EDUCATE PEOPLE ABOUT VOTING

An article on the problem of electoral rolls before the November 2015 national elections

An article on the problem of electoral rolls before the November 2015 national elections

A list of political parties in the national election of late 2015

A list of political parties in the national election of late 2015

A report on the Burmese electoral commission

A report on the Burmese electoral commission

Zarni’s journey

Zarni’s journey

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

In most countries citizens know what it means to vote, but this is not the case among the majority of Burma’s almost 32 million voters.

Civic education by the State is non-existent. The population as a whole, and the rural population in particular, does not even know of the existence of electoral lists, how an election takes place, how to vote and what roles elected representatives will have… The rural population is primarily concerned with daily survival, so there was little interest in these elections when campaigning began.

In February 2015, the first electoral lists were made public by local election commissions in some areas, whereas others had to wait until May, even July, only three months before the national election. Many errors were found on all lists, concerning up to 80% of all voters in some areas: people who had died were registered or information on voters was incorrect, preventing people from voting.

Civil organizations and political parties then had two weeks to undertake a "tour of voters" to explain the process and try to correct errors with the local election commissions. But a month before the election, one million voters were still missing from Yangon’s electoral rolls, for example!

A child at work collecting waste in the town of Kyauk Pyu in Arakan

After selecting a dozen people in Kampelet region, training on good election observation practice began.

It took a 24-hour bus journey to reach the mountains of Chin State. It was one of the ethnic regions where New Myanmar Foundation had local partners to organize training.

THE MEANING OF ELECTION OBSERVATION

A list of budgets and themes funded by National Endowment for Democracy (US government organization supporting civic education in Burma)

A list of budgets and themes funded by National Endowment for Democracy (US government organization supporting civic education in Burma)

Analysis of the November 2015 elections and their consequences

Analysis of the November 2015 elections and their consequences

An article on international observer teams for elections in Burma

An article on international observer teams for elections in Burma

An article questions the limits of the work of the EEOP network

An article questions the limits of the work of the EEOP network

Zarni’s journey

Zarni’s journey

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

At the beginning of his mandate, President Thein Sein said that his Government wished to hold free and fair elections in 2015. Unlike the national elections of 2010, observers would be invited to observe the process.

These were to include Burmese civil society organizations (CSOs), political parties, ASEAN observers, the Asian Network for Free Elections, the European Union and the Carter Center. They were to be present before, during and after the elections.

The Union Electoral Commission (UEC) defines the rules and regulations that govern observers. Together with CSOs, they have developed a code of conduct for national and international observers. Some laws have also been amended, for example the rules concerning voting in advance. The president of the UEC himself acknowledged that advance votes were the main fraud in the 2010 elections.

CSOs wishing to be active at these elections, for the first time in most instances, joined together to form a network for the education and the observation of elections (EEOP) in January 2014. Independent, numbering about 50 in total and based in big cities and ethnic regions, they were to coordinate their work following the elections. Only the Kachin region had no observer from this network. Other associations rallied to the People's Alliance for Credible Elections. Each of the two networks planned to cover different parts of the country.

These CSOs, as well as political parties and national and local election commissions, worked with international organizations for electoral support, mainly European and American, for two years. The goal was to learn about, each according to its role, good practice in the holding of democratic elections: training in election observation, strengthening the organizational capacity of political parties, reinforcing the competences of members, designing opinion polls...

One year before the elections, the Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL) meets with media and associations seek to bring together citizens and observers for future national elections

In 2012, for example, a campaign was organized to oppose hate speech directed by one community against another, at a time when riots between Buddhists and Muslims in Arakan state had claimed hundreds of lives.

The New Myanmar Foundation has taken part in this campaign from the beginning. Today, Mya has come to one of these meetings in a church in downtown Yangon.

Since 2011 and the resumption of fighting between the Burmese Government and ethnic minorities after a ceasefire lasting for several years, civil society has launched the concept of "Metta campaign".

Representatives of Buddhists, Christians, Hindus and Muslims, together with laypersons, have organize public meetings to discuss the theme of peace.

RELIGIOUS AND LAYPERSONS SPEAK OF PEACE

A report on a selfie campaign by Myanmar students promoting cross-cultural friendships

A report on a selfie campaign by Myanmar students promoting cross-cultural friendships

Report by The Guardian on the Rohingya

Report by The Guardian on the Rohingya

An 2014 article providing an update on discrimination encountered by the Rohingya minority

An 2014 article providing an update on discrimination encountered by the Rohingya minority

A perspective on religious tensions with the film

Those buddhists that exclude

Those buddhists that exclude

Zarni’s journey

Zarni’s journey

Nini’s journey

Nini’s journey

More generally under the two dictatorships, the army, whose ranks once included people of different ethnic origins on an equal footing, reinforced the presence of those of Burmese origin, specifically among high-ranking officers. For decades also, a “Burmanization” policy was pursued with violence in the ethnic territories. A large part of the ethnic population that had converted to Christianity during the colonial period was subjected to this policy, which ranged from simple discrimination to serious abuses of human rights. Army battalions used forced labour, theft, arbitrary arrest, rape, murder and torture to impose themselves.

90% of the Burmese population is Buddhist. Yet, this philosophy of peace is not shared by all, despite the practice of the religion being centred on "metta", meaning “loving-kindness". A love that in theory, is not directed at one person or group of people, but to humanity as a whole...

Since 2011, however, with relatively greater freedom of expression, a minority of nationalist Buddhist monks has been spreading anti-Muslim rhetoric. These leaders have been responsible for several violent confrontations among the population.

Mosque in the center of the town of Kyauk Puy in Arakan, burnt and closed after fighting between religious communities in mid-2012

Historically, the main instigator of discrimination in contemporary Burma has been the army. Inciting a group to hate another is a time-honored tactic for any authoritarian power seeking to weaken its opponents.

The dictatorship of General Ne Win implemented the so-called "Burmese way to socialism" policy by nationalizing all companies. Many members of the Chinese community, among others, lost all they possessed. As early as the 1950s, the civil war that destabilized the country was not just about ethnic movements. The biggest army, after that of the State, was that of the Burmese Communist Party, backed by neighboring China.

In the 1960s, the General Ne Win began to discriminate against the Chinese population of Burma, prohibiting them from access to property and also from practising certain professions, medicine, for example. He then closed all Chinese language schools. His propaganda gave rise to anti-Chinese feeling among the population, resulting in the exodus of some of the country’s Chinese community.

Fifteen years later, Muslims were to suffer from the dictator’s openly xenophobic policies, in particular those of Arakan. In 1978, the army launched "Operation Dragon" in the west of the country, with the aim of intimidating the Muslim minority, the Rohingya, through violence. Nearly 250,000 crossed the border seeking refuge in Bangladesh.